Exhibitions

-

Odyssey

SPRING/BREAK NYC 2025

May 6 - 12, 2025

Odyssey presents the work of Paolo Morales and Derek Olinger. Both artists use their practice to explore personal journeys - physical and emotional - in search of family and home. Olinger’s paintings are bright, fantastical worlds, layered with metaphor while Morales’ black and white photographs present a documentary-style view of the world from his vantage point, yet both artists are moving from past to present, old life to new, seeking a place of comfort and acceptance.

Thomas More’s book Utopia is set in the kind of liminal space that Olinger and Morales describe in their work, a topos caught between good (eu-topos) and mythical (ou-topos). To More, a perfect place, like Hesiod’s Golden Age, isn’t a real destination, it is the journey’s idealized end. Each utopia is a reference to and rooted in the time and place it originated from; it is a reaction to our experiences, memories, and hopes for the future. The works in Odyssey exist not only in a no/good place but also in what French Humanist scholar Guillaume Budé suggested to More as an ude (never) -topia; a neverland. The topoi depicted in Morales’ and Olinger’s work are chimerical notions, landscapes in chiaroscuro, flickering, just out of reach.

Morales’ documentary-style photographs often feature Asian women in domestic settings who appear lonely even as they support one another. His work imagines a racially, economically, and socially diverse world where people not only want to be taken care of, but also seek to care for others. As a straight, Asian-American male artist, Morales’ work is preoccupied with the ways in which the identity of an artist can be reflected in a photograph, and whether a landscape - or photograph - can be racialized.

Morales’ Balikbayan series explores transnational identity, diasporic culture, and family ties based on his experiences visiting family in the Philippines where he felt at once a part of yet separate from them. In Tagalog - the native language of the Philippines where Morales’ mother is from - balikbayan refers to a Filipino person returning to the home country. In these works, Morales considers how to photograph a place that he is ethnically from yet does not actually call home, begging the question: Is it possible to return to a place that you did not originate from? Can we go home again? Or do we find ourselves in a third space, between the familiar and imagined?

Olinger likewise takes inspiration from events in his own life, exploring topics such as disability, caregiving, death of loved ones, and family dynamics. He grew up visiting Southern California with his parents, who shared family histories rooted in the area. As an adult he decided to move there and start a new life, leaving his past behind for a brighter future. In his new home, however, the elements of his old life that he had hoped to escape were still present.

Olinger’s recent S.O.S. series consists of three paintings: Save Our Souls, Sacrifice Our Souls, and Without A Shore. Created on a smaller scale than his earlier work, the series addresses generational trauma in close, intimate imagery. The series tells the story of Olinger’s grandmother who nearly drowned in Laguna Beach and of her father and uncle who perished while attempting to save her. This traumatic incident affected the family for generations and Olinger’s paintings seek a reconciliation with the past. The two larger works, Mysterious Swimmers and Swimming Home are dream-like paintings where real life figures mingle with monsters in idyllic settings. Concerned with his partner’s chronic illness, family dynamics, danger, and fear, Olinger’s paintings of Southern California depict somber events and memories, remade in bright, buoyant images filled with sunshine and glamor.

At the end of the Trojan War, Odysseus traveled for ten long years trying to return home to Ithaca. His journey was neither direct nor what he had anticipated. He was waylaid time and again in otherworldly - and underworldly - places that seemed idyllic yet often turned monstrous. When he finally arrived in Ithaca, only his loyal dog and nursemaid recognized him and he found his home and wife under siege; not the happy homecoming he was expecting. Told in media res, the Odyssey is not a linear narrative and there’s slippage between real and imagined; then and now. In their work, Morales and Olinger similarly travel through time and space, seeking home and family, trying to understand the connections that unite them with their origins. This exhibition tells personal stories that evoke desire for another, better world, a space apart from the present. Much like Homer’s Odyssey, Morales’ and Olinger’s works suggest that places aren't always what they seem and that even familiar places, like those we call home, shapeshift in our memories, luring us like sirens to a place based on - yet more perfect than - reality: a utopia.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

January 13 - May 18, 2025

Connective Fibers explores how to dissolve perceived boundaries through sculpture. Fiber art and specifically wet felting, has a history as long as human civilization but it is often perceived as craft, hobbyist art or women’s work when really it is an integral form of storytelling that is fundamental to understanding history and culture. Using fiber art as a vehicle to tell uncomfortable and painful stories, as Zondag does in Connective Fibers, creates a dissonance that pushes the observer to wrestle with the themes presented; healing emotional trauma, the search for identity and the dissolution of borders between the body and our environment.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

January 15 - February 23, 2024

Strange Visitors encompasses a venture into the world of fractal abstraction. Unusual, mostly symmetrical patterns and forms, created entirely with 3D fractal software (no AI in this process), are printed on aluminum panels. The complex, intricate compositions invite viewers to interpret and define the artworks based on their own perceptions. James Porto is an artist who spent the last four decades making photographic illustrations for magazines, advertisements and exhibitions, primarily through the device of original photography and photorealistic compositing. He is now an assistant professor of photographic arts at Rochester Institute of Technology.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

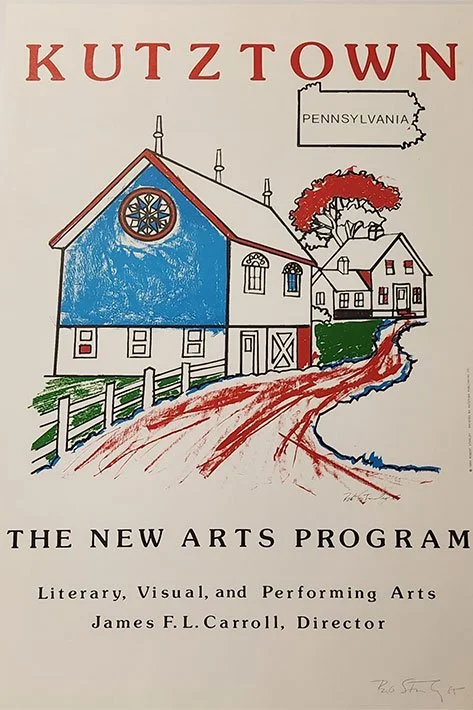

January 13 - February 15, 2025The archive of artworks from the New Arts Program (NAP) of Kutztown, PA, was donated to the Martin Art Gallery at Muhlenberg College in the summer of 2024. From 1974 to 2024, NAP offered artist residencies to many prominent and lesser-known visual artists, musicians, performers, and writers. They included Keith Haring, Richard Serra, Sam Gilliam, Joan Jonas, Phillip Glass, and Meredith Monk.

The New Arts Program closed its doors in June 2024 after 50 years in operation. While Muhlenberg is home to NAP’s artistic output, the Archives of American Art received documentary materials related to the programming, operations, and creative processes of NAP. Encompassing around 300 works — from paintings, sculptures, and prints to works on paper and artist books — this collection significantly expands and enhances the College’s permanent collection of art.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

January - August, 2025

Rain explores reconnecting to Indigenous community, queerness, and survival through figurative watercolor painting and beading. Am I native enough? Queer enough? Was it bad enough? These themes are explored through expressive color and fine detail that help people see themselves and their experiences in the pieces.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

August - December, 2023

Ashe Kaye (American, b. 1985) is a multidisciplinary artist, photographer, educator, and object maker who utilizes advanced 3D technology to explore intersections between gender norms, sexuality, and indulgence. In their work, Ashe Kaye responds to and challenges the tenets of their Mormon upbringing by subverting the gender binary and the religious and societal expectations that accompany it.

Highly metaphorical in nature, the bold, bright images in Glut and Guzzle are simultaneously eye-catching and grotesque. Body parts such as nipples become biomorphic shapes; indistinct yet familiar. Organic processes like gestation and birth are hinted at with vivid yellow yolks and broken eggs. The tactile quality of the works – from soft sculpture to sculptural frames – offers a multisensory, visceral experience.

The work in Glut and Guzzle is a deeply personal meditation on the artist’s lived experience as a non-gender conforming person. It is also an outward exploration of gender as a socially-constructed identity. From culture to culture and across different eras, concepts of “feminine” or “masculine” behaviors shift and change, demonstrating an inherent fluidity in the very notion of gender.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

January 23, 2023 - March 3, 2023

Françoise Gilot was born into an upper-middle class family just outside of Paris in 1921. Encouraged by her father from a young age to pursue legal studies, Gilot earned degrees from the Sorbonne and the British Institute in Paris as well as Cambridge University. However, at the age of 19, Gilot defied her father’s wishes to continue law school because she was determined to become a professional artist.

She studied under the Hungarian artist Endre Rozsda and in 1943 she and a friend had their first exhibition in Paris. It was during this time that Gilot met Pablo Picasso and began a romantic relationship with him. After nearly a decade and two children together, Gilot became the only one of Picasso’s partners to leave him.

Picasso famously called Gilot “the woman who says no” because of her strong will and independent spirit. This moniker perfectly describes an artist who defies boundaries and has created a style uniquely her own. Gilot rarely works from nature or models, preferring instead to draw from her memory and imagination. Rather than being interested in depicting narratives or providing viewers with clearly defined subject matter, Gilot focuses on the power of color and form to convey meaning. Her work is suspended between abstraction and figuration and she often employs leitmotifs, or recurring themes, in her imagery to suggest universal concepts.

While Gilot works in a variety of artistic media and continues to paint daily at the age of 101, her bold use of color and fine draughtsmanship are most present in her lithographs, which form the basis of this exhibition.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

October 14 - December 31, 2024

Often monumental in size, Sofia Cacciapaglia’s paintings depict dream-like gardens and larger-than-life female entities suspended in ethereal spaces. These two distinct leitmotifs in the artist’s work are united by themes of fecundity, regeneration, and renewal. They also harken back to the long Italian tradition of fresco painting, seen in ancient Roman homes and Renaissance chapels. The Italian phrase for fresco painting, or applying pigment to wet plaster, is affresco. This term is derived from the Italian adjective meaning “fresh”, an apt description of Cacciapaglia’s process. She doesn’t work from sketches. Rather, she paints intuitively, allowing each subject to become realized only in the moment of creation. Often utilizing cardboard scavenged from the streets around her studio, Cacciapaglia allows discarded objects to live di nuovo: renewed, afresh, transformed.

While the artist was born and raised in the northern part of Italy, she spends each summer at a family home in Sicily, a locale that is a source of continuous inspiration for her. Also called an “island of gardens”, Sicily’s countryside is lush and brimming with life; a place where flowers grow tall and wild without constraint. In Affresco su Cartone works, Cacciapaglia depicts fantastical landscapes in an impressionistic style reminiscent of Claude Monet and Gustav Klimt’s paintings of flowers dappled with sunlight. In works such as Affresco su Cartone: Blue Garden Diptych and Marzo, Cacciapaglia builds what the ancient Romans called a locus amoenus, or a pleasant place, where vast, illusionistic gardens dissolve the solidity of the wall on which they are painted, opening a window to the outside world. The best ancient example of this can be seen in the Villa of Livia (wife of the Emperor Augustus), which is located in Prima Porta, just to the north of Rome. The room is painted in its entirety, floor to ceiling, with such detail that individual species of local plants and birds may be identified. The use of perspective gives the scenery ample depth, allowing a visitor to the space, which had no windows, to imagine that they were instead standing in a sumptuous garden.

While Cacciapaglia’s work veers away from the precise realism of Livia’s villa fresco, she does cover entire walls with paintings by placing together individual cardboard pieces, mosaic-like, to create encompassing works whose vast size belie the delicacy of their imagery. Works such as Affresco con Nuvole (fig. 4) are composed of numerous cardboard pieces, assembled together to create a whole image. Cacciapaglia leaves the seams between the pieces visible, though, and she allows the cardboard’s underlying corrugation to show through the paint. While the image itself suggests a window with a view on to open skies, the construction of the work calls attention back to the process of painting on a two-dimensional surface, making the physicality of the work ever-present. During the Renaissance, artists who painted frescoes such as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling would delineate a giornata, which was the amount of wet plaster that could be painted in a day’s work (giornata means “day” in Italian). An entire wall - or ceiling - could be a single image, composed of multiple days’ worth of painting, and much like Cacciapaglia’s cardboard frescoes, the traces of each individually painted element are often still visible.

Images of women in Cacciapaglia’s work are also often monumental in size, lending them a regal authority. In some of these works, like Affresco su Cartone: Pink Skirts Triptych and Affresco con Arco, groups of women are joined by the hands, moving in harmony with one another. In other works, like Affresco su Cartone: Mask, a single figure appears, often with her eyes closed or blindfolded, creating a virtual wall between viewer and subject. What all of the figures have in common is their ethereal quality; a timelessness that refuses to position them in a specific place or time. By keeping the women at a remove, Cacciapaglia allows the figures to represent a unity - and mystery - that exists in the female experience. As with her landscape images, the artist recalls ancient Roman imagery in her figural works. The Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, is a particular source of inspiration for Cacciapaglia. Within the villa, there is a mosaic that depicts lively young women in Roman “bikinis” playing ball and lifting weights together. Much like the figures that populate Cacciapaglia’s paintings, they are a community of women; bold, strong, and in harmony with one another, enjoying an eternally youthful existence.

In addition to ancient precedents, Cacciapaglia’s paintings on cardboard are also a nod to the Italian arte povera (literally ‘poor art’) movement of the 1960s. The Italian art critic and curator Germano Celant coined the term in 1967 to describe the work of young artists such as Jannis Kounellis and Alighiero Boetti who employed unorthodox materials in their work like dirt, twigs, and scrap metal. While the materials were indeed humble, Celant was not referring to monetary value but rather the idea that the artists were utilizing cast-off objects to challenge traditional modes of production and consumption, particularly within the established art world. Cacciapaglia follows the arte povera model by painting on used card- board and packing paper. She thus elevates the debris of contemporary society to the level of a work of art, allowing detritus to live again di nuovo.

-

Martin Art Gallery, Muhlenberg College

May - August, 2023

In On Collective Memory, Maurice Halbwachs asserts that it is only while sleeping that the individual is able to free himself from societal understandings of totalities. Recognizable images and events appear in dreams, but in a fragmented, incoherent state. In the space between cognizance and slumber, the mind reflects upon its memories and turns them into images. Halbwachs goes on to ask, “Is it the image or the memory that preceded and occasioned it that reappears in the dream?” The paintings in Derek Olinger's Land of the Sun series tap into this unconscious act and lay bare the way our minds can conflate the two, receiving external messages and internalizing them.

Olinger’s paintings exist in the liminal space between dreams and wakefulness. Inspired by artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Olinger balances real events and locales with dream-like visions, depicting a fantastical version of the external world, at once autobiographical and universally themed. Family relations, life and death, even the disturbing events in the world today are themes present in the work. Eric Fischl's undercurrents of suburbia mingle with hints of Antonioni’s isolationism. The result is a land of magical realism replete with fictional narratives charged with psychological drama. Sympathetic monsters devolve into Dracula. Evil has taken over. Everything is upside down; turned inside out.

Simultaneously surreal and familiar, the images in Land of the Sun incorporate instantly recognizable figures - Dracula, the Creature from the Black Lagoon - in distinctly Southern Californian settings such as pools and mid- century Palm Springs buildings. Through his work, Olinger references Joseph Campbell’s “beauty and the beast” concept from The Power of Myth as well as the Jungian Shadow by representing the inner monster in corporeal form; projecting from the inside out. The archetypal monsters in Olinger’s paintings bring a mysterious and sometimes menacing feeling to an otherwise paradisiacal journey suggesting duality in supposed utopia.

Symbols appear throughout the work, like the universally recognized beach ball doubling as a sphere symbolic of the soul. Is the soul uplifted or weighted down, and under whose control? In every painting a shimmering pool is present, suggesting the reflective quality of water and bringing to mind Cocteau's Orpheus walking through the mirror into the netherworld. Swimming Home is reflective of the artist’s journey to his hometown to care for his dying father. The hour the artist’s father passed, a child was born to his sister-in-law. The full moon appears, representative of mid-life while the pyramidal mountain summit in the distance resembles both the ancient tombs of Egyptian pharaohs and the highest peaks above the artist’s hometown. It’s a reconciliation of the past, while looking forward to the future.

Olinger connects to Southern California’s genius loci not just through keen observation of the physical locale (San Jacinto Mountains, San Gabriel Mountains, Eisenhower Mountain) but also through inspiration drawn from Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series, mid-century modern architecture (Morse House; Green Gables; Royal Hawaiian Estates), and music (The Doors, LA Woman, The Eagles, Hotel California, Ambrosia, Life Beyond L.A). Southern California’s spirit of place is mythologized; it is an aesthetic, a color palette, a shimmering quality of the water splashing in a pool. In Olinger’s paintings, Southern California is a state of mind, a place where beautiful women frolic with monsters, where the monsters are people we know, and where the sun is always shining.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, Michel de Certeau states that “...text has a meaning only through its readers; it changes along with them; it is ordered in accord with codes of perception that it does not control. It becomes a text only in its relation to the exteriority of the reader.” Much like the writing-reading paradigm de Certeau suggests, making and viewing art are a combined creation and consumption process. The paintings in the Land of the Sun series are an example of this cyclical process whereby the artist consumes external stimuli which are internalized only to be externalized once more in new and altered forms.